As part of the Creative Dundee event ‘Act Locally: Today’s Fight for the Future of Equality‘, we have commissioned Hamzah Hussain to write his reflections on the event and theme. Below you can find the product of that commission.

The corridor is dark and the wooden floor cold against my bare feet. I can feel the cracks where the boards don’t quite meet and the undulations of where some boards are higher than others. I face the

emerald green wall staring. Staring as if by doing so the heavy wooden door will swing open for me. But I don’t possess such power. It stares back, daring me to come closer yet warning me not to take

another step. I ignore it. I place my ear against the door and close my eyes. At first, all I can hear is my own breath, fast. I slow it down, right down. Inhaling through my nose and exhaling through my mouth. Then they come. The voices, happy, laughing, excited –humdrum harmony.

My heart swells.

Eyes still closed, I pat down the door in searching for the handle. I grip it, my hand straining to cover the large sphere. It isn’t as cold as I thought it would be. But warm with moisture still loitering on it. The coldness comes from my hand, a hand that has never felt a door like this before. I step back and take in a deep breath before opening my eyes again. I reach out for the handle, gripping it with hard intent. I turn it left, then right, but it doesn’t give. I try pushing – nothing. I try pulling – nothing. I step back again. I turn around, my back to the impenetrable block of wood. I make to walk away. My foot stops dead in the air. I turn back. I clear my throat and furrow my brow, my sights lock in on it. The handle gives a glinting wink. I roll up my sleeves, raise a fist ready to rap on the door. It hovers there for a moment. I clear my throat, relax the muscles in my face and open my hand flat.

My hand meets the solid surface softly three times. I wait a while before the door finally opens. It doesn’t open inwards or outwards but slides into the wall. I could never have known that. They all stand there with identical smiles. I ask to enter, and their smiles turn down. I ask again, wiping the sweat from my forehead and showing it to them. They turn to each other, nod and let me in. The door slides shut. In the vast bright white room, the air is different. The people turn to their huddle, speaking amongst themselves. I try to join their circle but one of them puts an arm around me, smiling while he does. He leads me to a corner of the room which looks as if it were made just for me. In it is a small chair. He lowers me onto the chair asks me to smile, which I do. He takes a picture and posts it online. I watch him re-join the group. After sitting there for a few minutes, I get up and leave.

They never notice I find myself back in the corridor. To my surprise there are others outside, waiting to enter. But they aren’t like the people inside, they’re like me. I walk off, beckoning them to follow me and they do. We walk further along the corridor until we came to another door. This time I show them how to slide the door open. We go inside and make the space our own. We remove the door so that others like us can come in.

The above is a response to artist Alberta Whittle’s performative presentation at the Act Locally equality event in October. She walked around the space giving her presentation, inviting members of the audience to read for her. At intervals, we were asked to close our eyes and imagine a door. The door, of course, represents a barrier between two spaces. It represents access. Doors divide spaces but can be opened, closed or broken down. Doors, unlike walls, can move, be wedged open, unlocked. Often, we say ‘door’ but mean ‘opportunity’. It’ll open new doors for you. Get your foot in the door. It’s a sense of accomplishment when you can get through the door.

We all know what equality is. It’s a simple idea that most of us agree with it. It makes sense, doesn’t it? Treat everyone with equality. Treat everyone fairly. Treat others how you would want to be treated yourself. The concept is so basic and easy to explain yet some of us forget how to do it. We lose that sense of expressing our humanity and create divides from the slightest of differences in appearances, culture, ideas and self-expression.

I began writing this with a feeling of trepidation and uncertainty. What could I possibly have to say about equality? What can I say that hasn’t been said before? Living in Dundee all my life, I have never experienced inequality myself. As a Scottish-Pakistani, Muslim I have never been in a situation where I felt I was being treated differently because of the way I look or the fact that I am a Muslim. I’m lucky.

I know that in some places, people aren’t so fortunate. I hear about stories and incidents where someone is discriminated against or refused something because of the way they look, what they believe or how they identify themselves. My never having experienced that doesn’t exempt me from the anxiety of being unlike the majority of Dundonians. I feel frustration for others. And I get frustrated at the lack of representation of people like me.

I could easily be naïve and think; No one has treated me differently, it doesn’t happen here. But it does, it happens everywhere. Maybe not outright or to our faces but it happens. It lies beneath the skin of institutions, embedded in the collagen as structural inequality. It is becoming increasingly clear that, in Britain especially, the structural biases are built in favour of a certain group of people. This group fits into Protected Characteristics[1] in a very particular way. Opportunities within institutions are most easily accessed by white, European, heterosexual, able-bodied males – and adding to the Protected Characteristics – those of middles class backgrounds. You only have to look at the arts and cultural sectors (being the example I’m most familiar with) to see the evidence. It becomes difficult then, for anyone not fitting to this ‘norm’ – we as a society have come accept – to access the same opportunities.

My own perspective on equality is admittedly limited. I know only of being brown and being Muslim – so I can only speak to that. I began this piece reflecting on what I think of equality. Like everyone I know what it means. Equality is fairness. It’s everyone on a level playing field, the same starting point. Naturally when I think of inequality my mind automatically conjures thoughts of race and racism. I think of myself being a brown man and a Muslim and how those inherent qualities of mine can be seen as Other. this is only one form of inequality and there are many other minority groups that experience it.

My understanding of equality, particularly as someone who can be viewed as a BAME[2] person or ‘a person of colour’, has grown over the years. At first there was racism; aggressive and outward hate. But inequality seems more nuanced, much subtler. There’s a larger and more concerning picture forming. Prejudice isn’t simply someone calling you a ‘paki’ or thinking all Muslims are terrorists. It can also be your ‘friends’ on Facebook who share Britain First post and think that the hijab should be banned. That is worse and more damning. At least with an overt racist you know where they stand and you can make the decision to cut them off. But when it comes from someone with a smile and an arm around your shoulder that’s when it is worrying. How many other people are viewing you and people like you in the same way? How many can you trust?

While my understanding of inherent prejudices, especially in Britain, becomes deeper with readings like Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race[3] and Brit(ish)[4] – the more I become disconcerted with the realisation that the odds are stacked against those who do not fit a certain image of being British. And with this comes a heightened awareness of just how much I do not fit this image.

The more I contemplate this theme, the more I notice examples of inequality around me in the media I am consuming. Whether it is a local production of The Laramie Project[5], reading The Good Immigrant[6]. The conversations about equality surround us, which is encouraging, but sometimes they are just that: conversations. Starting the conversation can be uncomfortable. You shift in your seat, you pause to make sure you’re saying the right things and not causing offence. Am I allowed to say that? Is that politically correct?

In the same way that we all know what equality is, we are aware of inequality. We know it happens. We see it on Twitter in a video where a white man yells racist abuse to a black woman on an aeroplane. We read articles about a teenager kills themselves after being bullied about their gender identification or sexual orientation. It’s out there and we see it. We speak out against it and we raise awareness of it. We say ‘this is unacceptable, it’s 2018 this shouldn’t be happening’ – but it does. Sometimes it can be grim seeing incident after incident online. It can be depressing and it’s easy to lose hope. It’s frightening to think that there are people out there who have a problem with the way you look, where you come from, how you express your identity or choose to live your life. It makes being in a room where you’re the only non-white person an anxious experience. You’re aware you stand out and that people can see that. The rise in hate crime and the negative portrayal of Islam in the media makes you think harder about how you conduct yourself, how you carry yourself. You don’t want to be mistaken for an angry, West-hating man so you treat people extra nicely. You speak more politely. You show that you’re not like the guys you see in the news. You love this country, the country you were born in and have lived all your life.

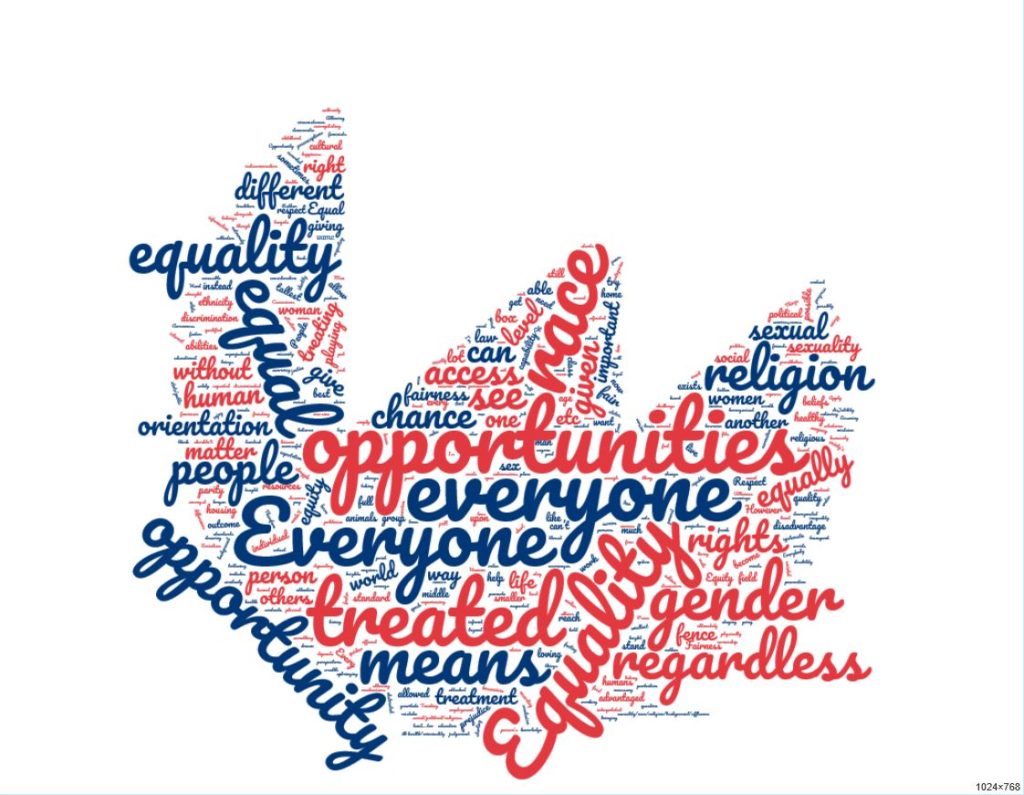

I began this project by documenting my thoughts on equality. I made notes and asked questions. I decided I couldn’t make this response only about me, so I sought help. I created a one-question survey which asked: What does equality mean to you?

I wanted to force people to define their understanding of equality. I wanted to know if there were any recurring words and phrases? Is there a theme? Are there aspects of equality that are considered more important than others? Is there equality in our understanding of equality itself? Is our understanding of the term correct, or does it need amending? Is its meaning different to everyone?

The intention was not to use people’s responses as statistics. The survey did not reach as widely as I would have liked since I simply used social media to invite people to respond. I received 88 responses, which I felt this was a good enough starting point and proceeded. I ran the responses through a wordcloud[7] program which let see which words appeared most frequently in people’s answers. With it, I could visualise what some of us prioritise when we think about equality. Aside from the word ‘equality’ itself which most included in their answers, there were many interesting and telling findings.

The word “opportunities” occurred most frequently and, therefore, appears the boldest in the graphic. The prevalence of the word suggests that lack of equality is understood as a lack of opportunities, a barrier between an individual and the opportunities available to them. It is the inability to open the door and enter the space that most have the privilege of enjoying.

Equality can, and often was described by respondents, as acceptance. It was viewed as taking all the ways in which we differ in our Protected Characteristics and accepting them as the norm. By taking all the qualities which deviate from our society has accepted to be a norm or a default and treating them as the norm. People should be given the same opportunities ‘regardless’ of which Protected Characteristics fall under. Other responses included describing equality as not doing something; taking all the Protected Characteristics and not judging them, not treating the person with those characteristics as different or Other.

One of the major factors of inequality isn’t overtly discriminating, although that is undoubtedly a huge problem, often it is a lack of visibility or voice. How do you make changes and progress if a group of people are not even being recognised? Refusing to acknowledge the issue is the first hurdle to overcome. An effective way of doing this is to continue highlighting areas of under-representation and to recognise that the playing field isn’t level for everyone. It’s one thing to not know that a problem exists in the first place. But to be consciously aware of the problem and fail to correct it is more damning.

The characteristics covered in the Equalities Act 2010 encompass all the parts of us that make us unique from one another. If you diverge from the perceived norm in any of these characteristics, there is a danger of being subject to prejudice and being treated differently. In my survey, three characteristics were mentioned more than any others: Race, Religion and Gender. Does this mean these are the most important, the most valid? Not at all. But I do believe these are the characteristics that encounter the most barriers because they can, more often than not, be identified from a distance.

If we want equality, we have to want it for everyone. We can’t only want equality only for the minority groups that we identify with and that directly affect us. Sadly, this is what happens when minority groups become splintered and different branched emerge. It is important to recognise the intersectional natures of inequality. If you manage to open the door for one group but don’t believe it should be open for another group, then the door might as well stay shut. It hasn’t opened at all if only for you and ‘your people’. If you’re on the other side of the door with the majority while others still don’t know which way it opens, then what did your opening of the door really achieve?

‘Most of the well-heeled residents of my home suburb prefer to say

they do not see race at all… In Britain, we are taught not to see race.

We are told that race does not matter. We have convinced ourselves

that if we contort ourselves into a form of blindness, then issues of

identity will quietly disappear’.[8]

Once we inhabit the same space as our peers we can still feel excluded and made to feel unwelcome. The choice to ‘diversify’ the space is done out of pity and as tokenism. Specifically created to show others how magnanimously they have accepted the Other. There are obviously institutions that mean well and have a genuine desire to be more inclusive but are anxious about being accused of doing it out of sheer tokenism. It is undoubtedly a tricky task. My first response would be to say: ‘If you’re looking to be more inclusive and have a person with Protected Characteristics in your institution, then just do it’. I would say: ‘Just do it, don’t make a big show about it and simply make it normal practice’. Then again, I could also see the issue some might have in this well-intentioned gesture. To not recognise the inclusion of more ‘diverse’ people is to once again show a lack of visibility. It is to downplay an inherent part of someone and to regard it is unimportant:

I try to join their circle but one of them puts an arm around me, smiling while

he does. He leads me to a corner of the room which looks as if it were made

just for me. In it is a chair that I am led to. He lowers me into the chair asked

me to smile, which I did, then took a picture before posting it online. I watched

him turn back to the group.

Being in a space inhabited by people who are considered within ‘the norm’ can be frustrating for those who don’t fit that image. Whoever doesn’t fit into this mould of the norm are seen as a diverse addition to the space. While they may have found access into these spaces, they are often few in number. In a search for unity and a connection to those with similar experiences, minority groups often resort to celebrating their differences by creating their own platforms and spaces in which their stories can be shared, and voices heard. We begin to see the emergence of platforms that are specific to these groups. These groups feel that they have to build their own platforms and opportunities.

We go inside and make the space our own. We remove the door so that

others like us can come in.

Accessing these opportunities in an environment that only recognises a certain type of people is difficult and taxing. Even talking about the problem is exhausting. Often people with Protected Characteristics have to work harder to earn the desired opportunities. They can find themselves working harder for less reward than their peers.

It doesn’t open inwards or outwards but slides into the wall. I could

never have known that. They all stand there with identical smiles. I

ask to enter, and their smiles turn down. I ask again, wiping the sweat

from my forehead and showing it to them. They turn to each other, nod

and let me in.

When frustrated, it can be easy to be aggressive when opportunities that certain groups are being given are not open to all. But I believe the answer is to be persistent and to continue creating our own opportunities and to celebrate those who have already done so. The access to opportunities can become easier with shared knowledge. If you found out how the door opens, tell others. We cannot, as it happens is some cases, is be exclusive in our approach to equality. There can often be divides between minority groups where views and approaches differ.

To write about and indeed to talk about the inequalities we see around is no easy task. It is uncomfortable at the best of times. But we should get used to this discomfort because it is pale in comparison to those bearing the brunt of equality face on a daily basis. The conversation continues to evolve as should our knowledge and understanding. By asking ourselves what our understanding of issues as complex as equality is we can examine just how much we know or think we know. By examining the language we use to discuss it, we can reflect on our grasp of this supposedly basic concept. A concept that is easily theorised but less successfully practised.

H.M. Hussain

[1] The Equalities Act 2010 recognises nine Protected Characteristics: Age, Disability, Gender Reassignment, Marriage and Civil Partnership, Pregnancy and Maternity, Race, Religion or Belief, Sexual Orientation and Sex.

[2] Black, Asian or Minority Ethnic

[3] Reni Eddo-Lodge, Why I’m No Longer To White People About Race, 2017

[4] Afua Hirch, • Brit(ish): On Race, Identity and Belonging, 2018.

[5] A play about the reaction to the 1998 murder of a gay student of the University of Wyoming in Laramie Wyoming, USA.

[6] A collection of short stories and essays about what it means to be an ethnic minority in Britain today: The Good Immigrant, ed. by Nikesh Shukla, 2016.

[7] An online tool where you can upload text and it creates an image with those words. The most common words are the largest and the least common are the smallest.

[8] Afua Hirch, Brit(ish), Vintage Books, 2018