17.01.24

If you work in arts and culture in Scotland, you have probably had countless conversations about the ‘funding landscape’ and ‘demonstrating impact’. As confusing national developments create an uncertain ground for what’s to come in the next months and years, communities across the country, who fundamentally rely on cultural provisions, are left wondering what to do.

There is a natural tension between the people-based work from these organisations and the numbers-based approach to measuring them. I recently explored this in another piece for Creative Dundee where the people behind creative spaces like Tin Roof and Unit 5 explained the ongoing ripples their communities created in the lives of participants; from fighting loneliness to inspiring a more hopeful professional outlook in the city. Generation-defining work that would be easy to miss if you were just looking at numbers.

In order to access vital funds these same communities or organisations (alongside the groups, practitioners and creative spaces in them) are asked to thoroughly and arduously report on their activity, but as the funding gets more scarce it also becomes more competitive and demanding. The context that surrounds this process also massively discourages it. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has recently found that over one million people still live in poverty in Scotland and in-work poverty continues to grow with a little over 10% of Scottish workers on low pay.

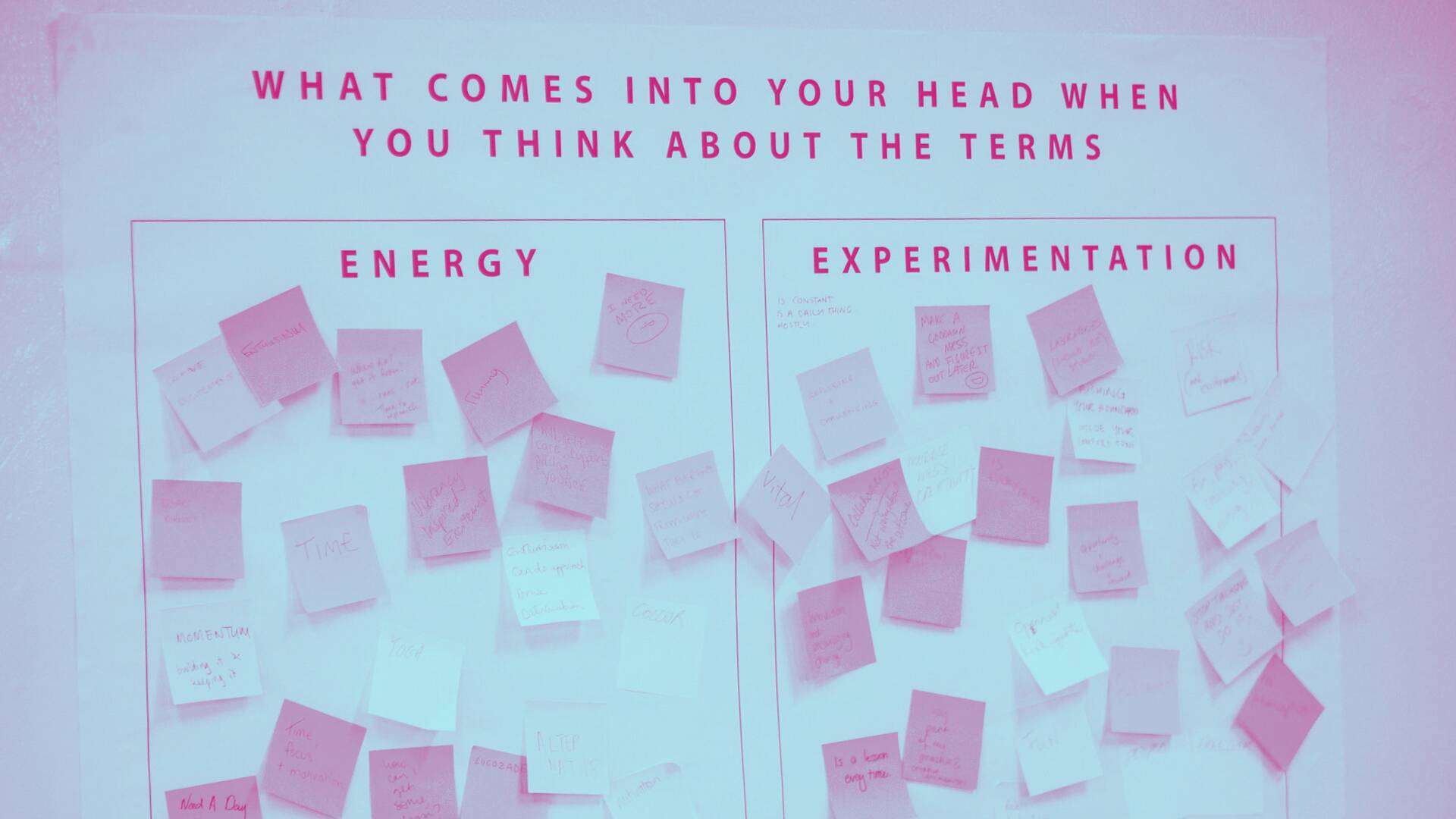

Social Action Inquiry Scotland has collected stories from different communities in contexts like this, investigating the factors that help and hinder social action across the country. One of their co-leads, Darryl Gaffney du Plooy, explains: “In the Inquiry, we have highlighted the stories of 17 communities. This includes activists, informal groups and groups with charitable status. Funding is mentioned in almost all the stories”.

These case studies have identified: “challenges with measuring impact in short-term funding cycles; articulating the nuances […] aligning the tangible impact of a project with the intangible outcomes”. Among other things, the Inquiry has clarified a common issue: there is a gap between the ripples of impact created by communities, and the type of evidence funders require.

This ‘impact gap’ is generated by the fundamental tension between the people-based work from these organisations and the numbers-based approach to measuring them. While it may seem like a technical and inconsequential discussion, when this gap is surrounded by massive cuts to public funds, deep poverty and overall scarcity it can have catastrophic effects in communities across the country.

There needs to be a more open conversation about how we measure impact, but also the impacts of measuring it.

Media theorist, Marshall McLuhan, coined ‘the medium is the message’ – a phrase repeated to the point of losing all meaning. But this axiom means to communicate that a message can only take the shape of its carrier. The content of what is being communicated assumes the form and characteristics of the way it is being communicated. When there is a scarcity of public funding and each opportunity is so competitive, communities only have capacity to do the things that can end up in those reports and applications. The work itself takes the shape of the measurements required by funders. The way we talk about something becomes what that thing is.

The excellent independent magazine Extra Teeth at the end of last year put out a statement saying they will be going on hiatus in 2024. One of their reasons for this decision is: “competition for funding is intense, and applications take weeks of unpaid labour to put in, with no guarantee of receiving the funding”. The process of applying for funding ends up taking the energy and capacity that might be going to work – especially work like this, that is experimental, representative and daring.

Heather Parry, co-founder of Extra Teeth, wrote in her newsletter: “there’s the enormous and administrative burden that’s placed on artists to allow them to beg for money from the paltry pot. To even apply for Creative Scotland funding requires weeks of unpaid labour—for funding that you are likely to not get, even if you are approved by the appraisals panel”.

“Accessing funding becomes industrial … suddenly there is little capacity to see the nuances in the work itself.”

The gap that exists between what communities do and what funders identify as measurable positive impact, eventually gets closed by organisations shifting their work because they can’t afford not to meet those expectations. This toxic mix of untethered expectations, gruelling funding rounds and an increasingly desperate need for them, translates into a diminished capacity for experimentation and a healthy process along the way.

Accessing funding becomes industrial. Never mind communicating the ‘nuances’ Darryl mentioned, suddenly there is little capacity to see the nuances in the work itself. FailSpace, a project exploring how we talk about failure in this context, reflects: “Prioritising narratives of success is often a result of a lack of honesty between participants, artists, cultural organisations and funders. Fuelled by a fear of losing funding and future work, this approach can limit risk-taking, learning and positive change towards a more equitable cultural sector.”

Not only should we be demanding that culture and the arts in Scotland are properly funded, there should also be a push to reframe how we discuss impact and the way it leads to funding.

Firstport, which supports social enterprises when they are just starting out, understands some of the fundamental barriers when it comes to reporting: “translating their own story into a narrative that fits into reporting requirements can be another barrier.” This wording is insightful. While organisations see impact as interconnected, chaotic and ongoing stories, they are often asked to tell these stories as straightforward narratives. A dimension of their true impact is lost in translation with what was a three dimensional experience of growth now having to read as ‘this person was X and now, thanks to us, they are Y’.

But if the impact of a project can only be perceived in a single dimension, they’ll struggle to nurture anything more nuanced. Projects get moulded in the image of the tools we use to record their impact.

“We need to make more space for complicated narratives, and understand that how we measure impact is just as important as the impact we are measuring”

As Firstport identifies: “evidence of serious consideration around how to measure impact is sometimes more important than having found the perfect measurement methodology”. The project should shape the tools that measure it, not vice-versa.

We need to make more space for complicated narratives, and understand that how we measure impact is just as important as the impact we are measuring – which should be done collaboratively and thoughtfully. As Hot Chocolate Trust’s Teckle Data showcases: “meaning-making and story-telling (because every record is a kind of story) should be something that we do with our beneficiaries, not about them”.

There has to be an understanding that measuring the impact in communities will always be flawed. An excellent research article by Tania de Saint Croix and Louise Doherty, in regards to measuring impact in youth work, reads: “we will never consistently, entirely, scientifically ‘capture the magic’ of youth work, and that overly formal attempts to do so can be damaging. Perhaps the magic can only be captured partially, fleetingly, some of the time”.

In the context of art funds being slashed, uncertainty in the stability of creative enterprises and closure of community spaces, the pressure may increase for organisations to narrow everything to box-ticking, and to grind their work to a halt while they do it. But the industry can only change when a nurturing space can be made for these communities to complicate the narratives.

Putting this piece together I got to have so many interesting chats with folks who are way more immersed in this conversation. So, I thought I’d share a list of links and recommendations that came out of these conversations:

Sam Gonçalves is a writer and filmmaker. He has written for The Skinny, Counterpoint and Boom Saloon. You can find more of his work on Everything Mixtape, a bi-monthly newsletter sharing interviews on topics like: art, activism, politics and culture.

If you would like to support us in creating even better content, please consider joining or supporting our Amps Community.