16.09.25

What is the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word “activism”? For a lot of people, this might conjure images of placards and PR stunts, something quite dramatic. However, there is a more subtle and enduring approach to take and people will regularly engage in activism without knowing or intending to do so. The actions themselves just need to be driven by a desire to inform, learn, or change something about the activist’s community.

Persistent, regular actions, no matter how small they might seem, can become everyday activism. A simple desire to occupy and show care for a space can be a catalyst for change on its own. So then, what kind of spaces can we occupy? Somewhere free to access, somewhere that offers you something in exchange for your company, somewhere surrounded by other people. What happens when you leave your desk, a bunch of pens in hand, and set up in a place where everyone who passes by can see what you’re creating?

I had a series of conversations with three people who bring creativity into their day-to-day lives about the spaces they occupy – a community garden, public green spaces across the city, and a library.

I spoke to Manuela de los Rios about her work with the Maxwell Centre, a busy Hilltown hub with a miraculous church yard garden. The Maxwell, like many community centres in Dundee, offers a broad range of activities year round, in an effort to provide something for as wide a variety of people as possible. You could turn up on any day without necessarily having to know what’s on and something will be in the works. The aim is to invite visitors to become more comfortable in their curiosity. To provide a space where everyone is open and supported to try something new.

There is a long, wooden table near the end of the garden, covered to keep the rain off and surrounded by this year’s crop. This table has seen countless art pieces, including hand made signage for the different beds in the garden. Manuela suggests that creating in the outdoors can make people more open to trying without having to worry about being good at it right away, that the environment makes people more forgiving. It can be a grounding, soothing, and perhaps even spiritual experience to create outdoors. Green spaces can be an ice breaker, in that everyone shares a connection to creation, nature, and food. There is a freedom in being outside that can bring others into a creative process: “sharing outdoor spaces with others allows you to share a sense of possibility”.

It is with that sense of possibility that I joined RSPB’s Hope Busák at a family day in a park in Stobswell, as part of the ongoing Arrivals and Departures project (an exploration of the overlap in experiences between human and bird migrations). Around us, trees swayed in the breeze while screaming swifts swooped overhead. Hope’s table featured berry laden twigs and herbaceous plants, the kind of dinner a jay or hoverfly would appreciate. She unrolled a large paper sheet covered in drawings for a small boy who wanted to check how his creations from a previous event were doing.

The paper documented an invitation for young community members to share and visualise what they want their outdoor spaces to look like – drawing an idealised version of their neighbourhood that makes room for people, plants and critters. It is a form of future visioning that can be a powerful tool in social research and policy making around public green space usage. This boy, apparently, had been very enthusiastic about making a grassy meadow for invertebrates to live in.

In moments like this, creation and conversation become the same thing. Hope notes that “the opportunity to create is an invitation,” that people tend to be more open to talking and learning when they’re busy doing something with their hands. Through creativity, they’re not so worried about saying the ‘right thing’ and to create a representation of what they’re learning also makes that information more meaningful. A large piece of paper covered in children’s drawings then becomes evidence of what a community believes is possible – evidence that can be used to convince local governments that their constituents care for and find inspiration in the spaces they occupy.

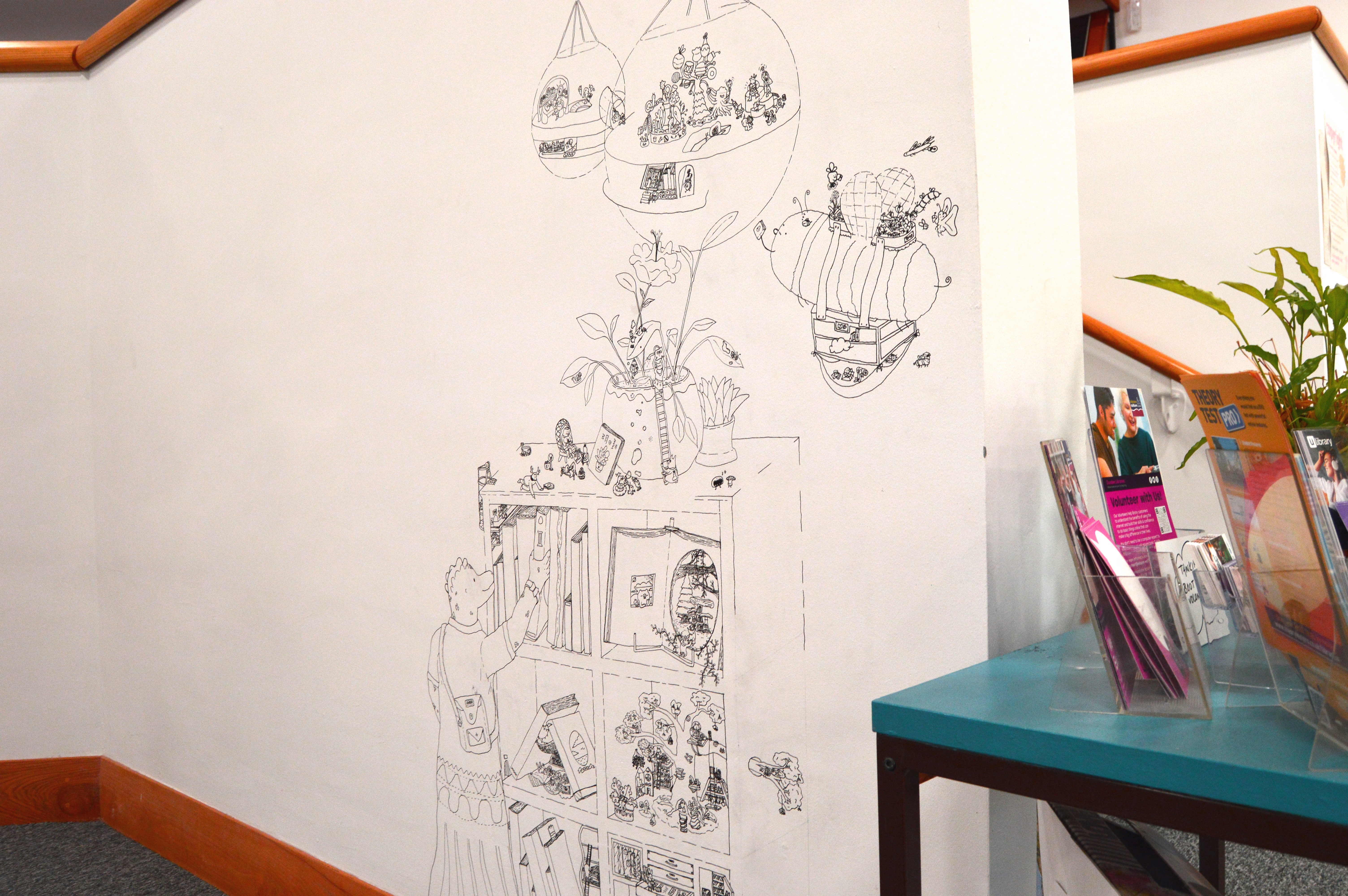

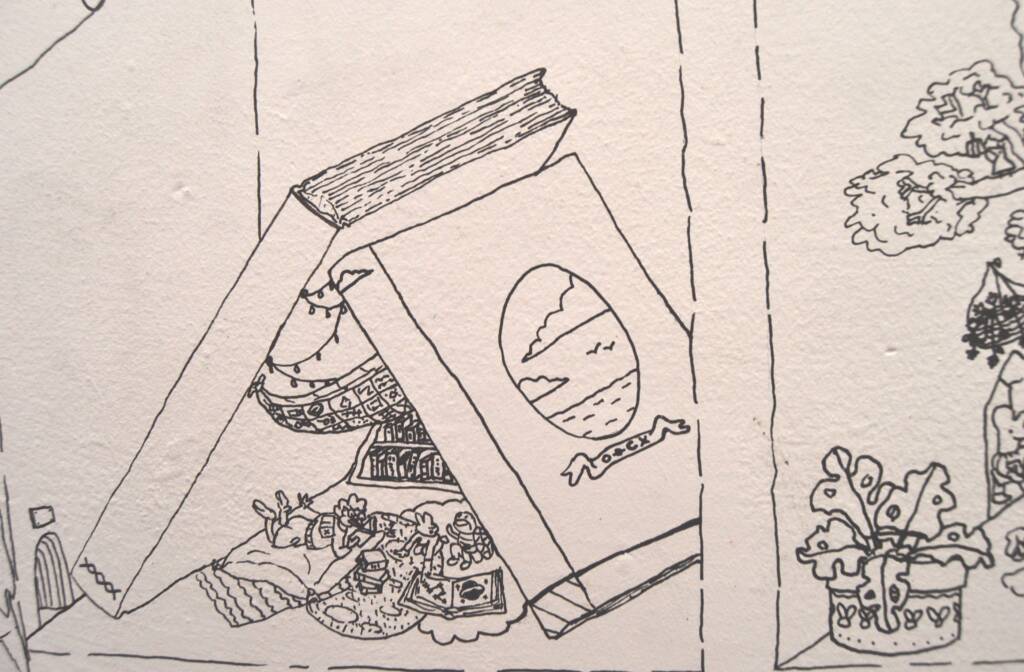

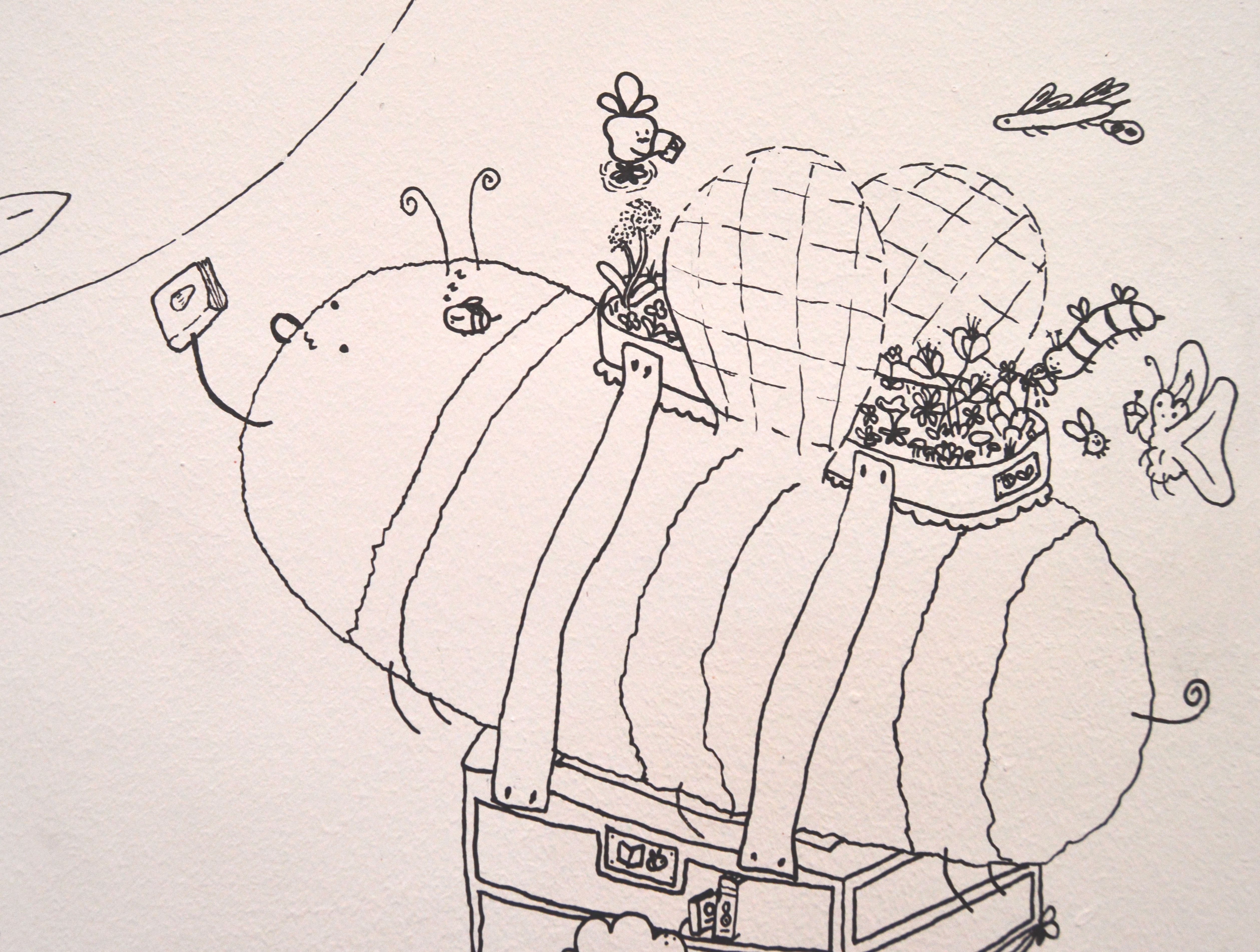

My next visit was indoors, yet still decorated with greenery. Potted plants along the reception desk, the tables, some shelves, slowly and steadily being inked into the walls. I asked James Morwood about his growing mural in the upper floor of Dundee Central Library.

To draw on the walls in a public space is a highly visible act, one that invites a lot of questions from both staff and visitors. It takes a leap of confidence to begin, but that leap becomes part of the invitation. Questions become conversations, and conversations become the sharing of ideas and action – transforming the library space in its use and appearance.

The subjects in the mural are not decided upon in advance and seem to arrive on the day like any other visitor, but a simultaneously intricate yet simplified style is part of the plan. It is approachable and warm, asking the viewer to see each little detail within the mural, and around them in the space. It asks you to wonder if you might try doing something like this yourself. The nature of the library fundamentally invites learning and growth, and encourages visitors to change their surroundings through workshops, exhibits, screenings, music making, and almost anything else you can think of.

There is a power in purposefully choosing to value third places in an increasingly commercialised world, and a part of that power comes in the way these spaces function as open access community hubs. It isn’t just about simply stating that a library, a garden, or a park is open to everyone, but about actively inviting people in. You create a space for people to express themselves freely, to share and show their experiences, and they will do so, eventually. The invitation to create is an invitation for change, and this is one way that third places can be both inherently activist and artistic.

However, extending the invitation is not always as easy as we would like it to be. There are a multitude of factors that influence whether or not someone will be willing to take you up on your ask, or whether your ask is reaching demographics representative of the surrounding community. Waiting for people to come to you can create a sort of sampling bias of people who were already with you. The consensus seems to be that you have to go out and find the people who have absolutely no idea who you are, and create something with them.

It can be daunting to leave a safe, yet potentially isolating desk-based environment, but Manuela says that opening conversations with strangers is an expression of free will. That expression can be empowering, and according to Hope, “any occasion where someone feels empowered to make change is a form of activism”. It can start small and build up: one day you’re borrowing a book from the library, the next, you are encouraging others to tend to one of the few true third spaces left by being visible, present and creative.

Hollis Crowe is a mixed-media visual artist with a focus on natural forms and bright colours. With an academic background in environmental science, he appreciates the connection between art and science as different modes of observation, and values the power of creation as an educational tool.

If you would like to support us in creating even better content, please consider joining or supporting our Amps Community.