20.11.25

Content note: This article will sometimes use the term ‘disabled’, to encompass all disabled, d/Deaf, neurodivergent, and chronically ill people. Although not all d/Deaf, neurodivergent or chronically ill people will personally identify as disabled, we do all face barriers because accessibility is not considered. We are disabled by environments and attitudes around us – as described by the social model of disability. It is important to have an intersectional understanding of disability and accessibility; disabled people may face additional and intersecting inequalities and discrimination due to other marginalised aspects of their identities.

Accessibility can take many forms. It is nuanced and complicated, and it can be difficult to meet multiple conflicting access requirements at once – especially in arts spaces. But it’s not impossible to improve access; to creatively consider accessibility in a space or event, or in the ways we communicate.

Scotland’s Census 2022 found that 21.4% of the Scottish population have a ‘long-term illness, disease or condition’. But even this may not account for all disabled, chronically ill and neurodivergent people, with the Family Resources Survey (2022-23) reporting that 27% of people in Scotland are disabled. So, if at least a quarter of our population self-identifies as disabled, where is the accessibility?

I regularly encounter inaccessibility in arts and cultural spaces, and it’s usually the same issues again and again. For example, a lack of seating in museums and galleries is particularly thoughtless – it is a simple accommodation that would benefit disabled and non-disabled people alike. I want time to enjoy the work, to take my mind off the ever-present dull aching in my body, to crack open a little gap in my cycling thoughts and consider what is in front of me. So much time is spent on curation, building exhibition spaces and transporting artworks and historical objects – do you really want audiences to leave after 15 minutes because they physically cannot stand any longer?

There are many small adjustments that would make disabled artists and audiences feel considered. Institutions and organisations won’t always get it right, but reaching out and inviting us in is the first step. Have these conversations with us.

When I spoke to neurodivergent, disabled and chronically ill people in my community, it seemed that many access issues could be easily remedied and, importantly, without large financial considerations. Simple changes to include detailed access information on websites, captions for more (or all) screenings of films and video works, and regular quiet hours (including some with mandatory masking) at museums/galleries would create a considerable improvement in accessibility.

For smaller organisations, funding is often the overarching issue. A broader, more considered approach to access could be costly, and many organisations are already contending with reduced funding and rising costs. Meaningful changes such as repairing or replacing lifts, improving bathrooms and changing place facilities, BSL interpretation, accessibility and disability awareness training or creating quiet/rest spaces, all require money.

Since neither the arts, nor the lives of disabled people, are a priority for our current governments, accessibility falls by the wayside. However, by not prioritising access in their spaces and programmes, arts and cultural institutions are actively excluding disabled people from participation – and this must be taken seriously.

These issues are even more evident for arts workers, as the sector is inherently inaccessible to marginalised people. Ableism is built into the industry; in complex and time-intensive applications, expectations of unpaid labour and full-time working capacity, and lack of adaptations to art school/studio/residency spaces. From the outside, there is seemingly a lot of talk about inclusivity and ‘particularly welcoming applications from people belonging to marginalised groups’. In reality, little action is being taken by institutions to remedy these issues and bring marginalised people – who have this expertise via their own lived experience – into decision-making roles.

A seat at the table wouldn’t immediately fix everything for disabled people, but it is necessary for beginning to create a more equitable and representative arts sector.

Neuk Collective is a community of and for neurodivergent artists in Scotland. They provide support and advocacy for disabled and neurodivergent creatives, such as support to create access riders, body doubling sessions, professional development workshops and online meetups. They also provide resources for organisations, including a guide for working with neurodivergent artists, and lend sensory/access equipment packs for events. Neuk is currently exploring how governance in the arts could be more accessible and representative of our creative communities:

“There are loads of disabled people in the arts but we’re not making it out of the lowest level; we’re not making it into management roles and decision-making roles, governance roles. So, we’re kind of weighted towards the powerless end of the spectrum” – Tzipporah Johnston of Neuk Collective.

Due to a lack of disabled people at higher levels in the arts, non-disabled people rarely understand the importance of thoughtful access measures. Our voices go unheard, and our needs unmet. This is why collective organisation and action is so important for disabled artists; connecting with other people in our community makes our voices louder and increases our capacity to build awareness amongst non-disabled people and non-disabled led organisations.

Johnston, of Neuk Collective, also stated the importance of non-traditional forms of governance and decision-making, for disabled artists:

“If we’re just trying to get disabled people to fit into existing governance structures, then a certain type of disabled person is going to end up on the boards. Is that representative of the whole disabled community? […] It’s not that I don’t think we should do that – we absolutely should – but, as well as that, can we think about alternative ways to get disabled people a voice in governance? That’s what we’re looking at, in this accessible governance project that we’re starting. For the people who are never going to want to be on this very bureaucratic, responsible, [time intensive] board, but they still have opinions that are important and need to be heard – how do we facilitate that in a way that is accessible for them? I don’t think there is a roadmap for that, at the moment.”

Most institutions take a hierarchical approach to decision-making, rarely engaging in meaningful consultation with artists, audiences, and other stakeholders in the community. This may be why younger organisations or non-hierarchical, artist-run initiatives are more proactive in tackling ableism and accessibility.

In Dundee, my interactions with Generator Projects have been particularly positive as both an artist/worker and visitor. When I attended a book event at Generator (a conversation with one half of The White Pube, and fellow disabled artist, Gabrielle de la Puente), I was provided with a comfortable, supportive chair and was able to go along and take my seat early, before any crowds had gathered. The event listing included an email address for access requests; this was an explicit invitation, a display of care. It was also a hybrid event so, if I hadn’t been well enough to go in-person, I could have watched along at home.

These types of events were a life raft for arts organisations during the lockdowns, and it is frustrating to see online/hybrid events and, thus, audiences who cannot attend in person, largely abandoned in the years since.

I also took part in a residency with Generator Projects last year, and this was the first time I had ever been invited to create an access rider. These documents help disabled people to disclose our access requirements to those we work with, in a way that minimises the labour and self-advocacy that is often required. When the access rider process is initiated by an organisation, this can reassure disabled people that our needs will be met and understood; some of the access labour has been taken on by another person, they are meeting us part of the way. It shows care and consideration that is so often missing from these interactions.

Creative Dundee have also recently developed their access rider process – including an open access template on their website, which I would encourage all artists, arts workers and organisations to read and consider implementing in their work. I was part of a group of creative practitioners who provided insights and critique for this project. It was refreshing to be invited to contribute to this work and engage with others to collectively shape both the access rider documents, and processes surrounding their use.

Understanding and implementing accessibility is crucial to the inclusion of disabled people in the arts but this work cannot be isolated from growing rhetoric against us.

We currently face an increasingly hostile environment of political scapegoating and demonisation, that hasn’t been so overt since the early 2010s, alongside cuts to vital support that enables disabled people to build and maintain careers. In addition to paid work or awards from funding bodies, the government’s Access to Work funding has been a lifeline for disabled creatives in the past. But recent proposed changes to this support have already had a devastating impact:

“There’s a general atmosphere of stress, I would say, for disabled people. One of the things I do is help members to apply for Access to Work. That has basically ground to a standstill. We were already seeing people waiting over a year, to even be seen by Access to Work assessors. There are definitely people for whom that’s the difference between working and not working. So, it’s going to have a big impact on the disability arts sector” – Tzipporah Johnston of Neuk Collective.

Disabled people in the UK are more likely to be self-employed, or on a zero-hour contract, than non-disabled people. Cuts to vital support, such as Access to Work, are likely to affect these disabled people – in precarious work, without benefits such as sick pay – even more greatly.

In this climate, it is more important than ever for individuals and institutions to educate themselves on the issues disabled people face, and take a more complex, radical approach to access, not simply seeing it as a box-ticking exercise. Be honest about not having all the answers. Access is never final; it is a gradual process of change.

I would like to thank the disabled, chronically ill and neurodivergent artists in my community for sharing with me their thoughts and contributions for this piece – and Creative Dundee for allowing me to write this piece on crip time.

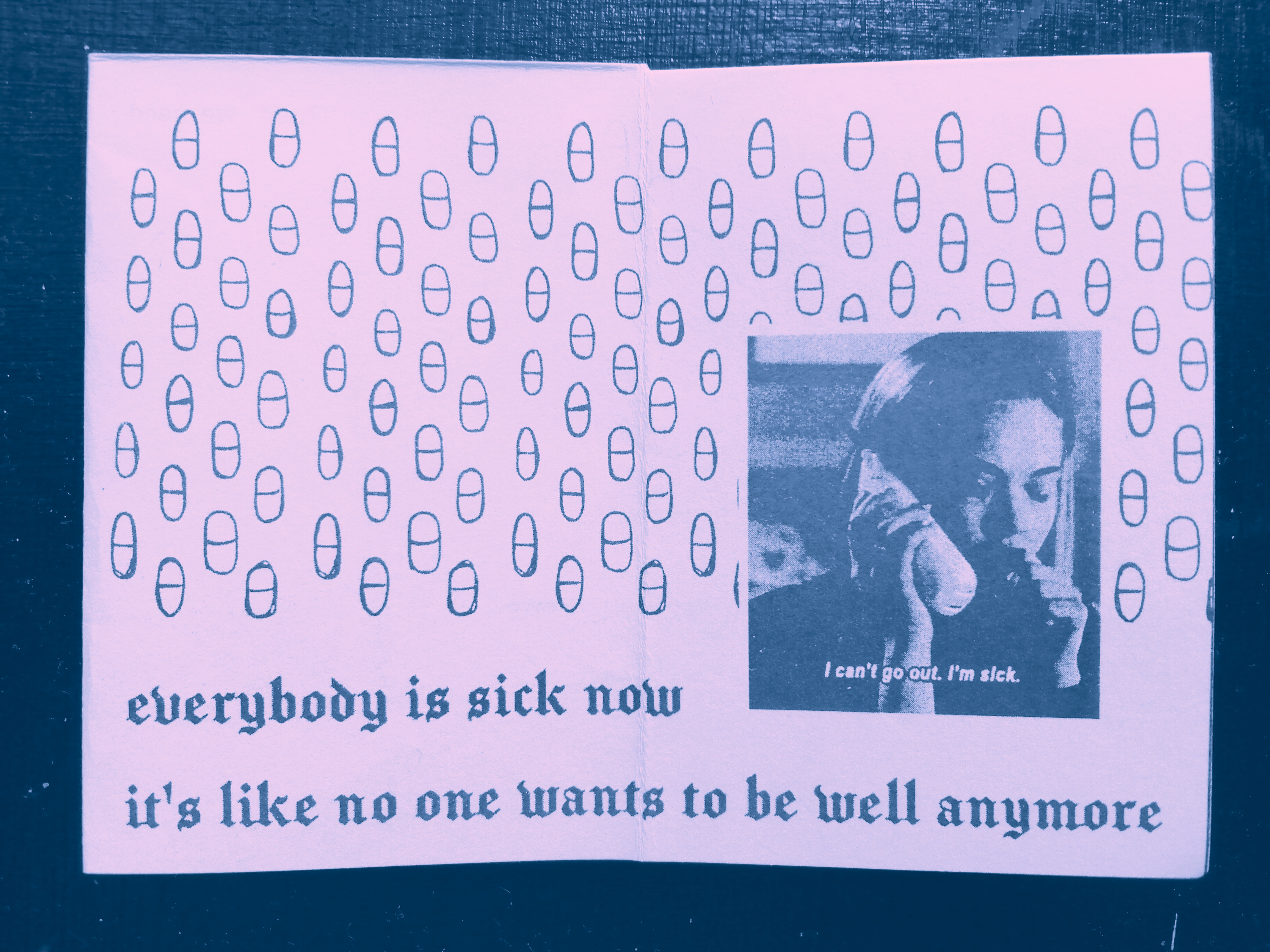

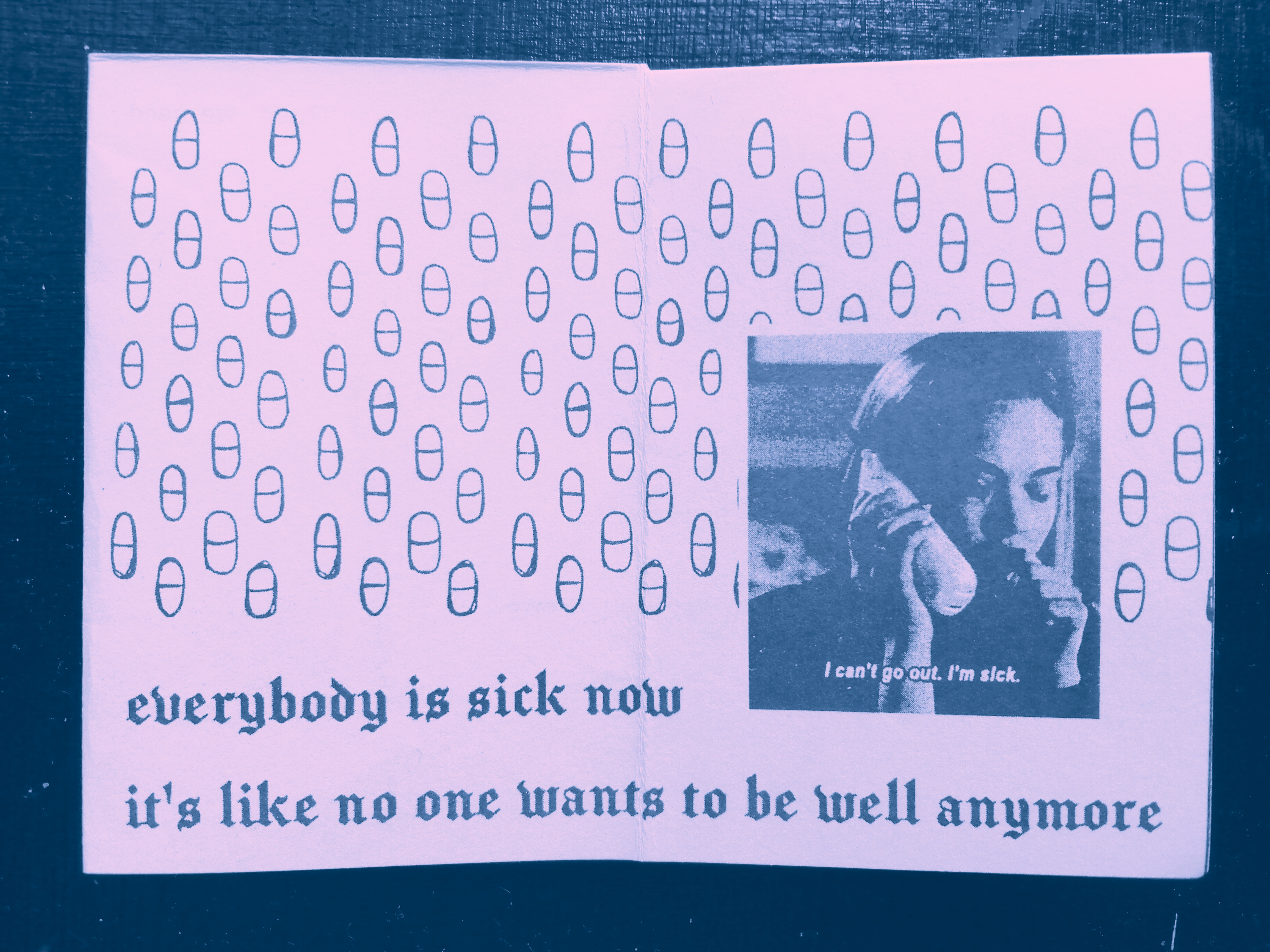

Laura Moorhouse is a disabled artist, based in Dundee. Her work explores rest, care and the confines of the unwell body, informed by experiences as a disabled/chronically ill person. As an emerging artist, she is learning to work on crip time – with the bodymind, rather than against it – prioritising flexible, comfortable ways of making.

If you would like to support us in creating even better content, please consider joining or supporting our Amps Community.