24.08.22

Often, these projects sit on a foundation of an individual’s particular passion for their chosen creative field but end up providing more benefit to the broader community than was ever expected.

In today’s interview, we’re chatting with Elizabeth Ann Day and Luke Cassidy Greer of Volk Gallery. Volk is a non-institutional arts venue based in the Keiller Centre in Dundee. Consisting of a repurposed nappy vending machine, it features 50 pieces of art from a new artist every month, available for £3 each. The idea for the project came from a joint trip to Vienna just before the first coronavirus lockdown of 2020. With none of the usual museums and galleries open, they discovered the art vending machines around the city’s museum quarter and they became (and we don’t think they’d mind us saying this) a bit obsessed with the idea.

Here, we talk about their journey with Volk, working within commercial spaces, and balancing working on passion projects against paying the bills. We also take some time to imagine the creative potential of Dundee’s high street, in a future version of the city where art projects and independent businesses live side-by-side.

Creative Dundee: So after discovering art vending machines in Vienna, you knew you wanted to bring the idea back to Dundee. How did you go about getting started?

Elizabeth Day: We were forced to take the time to really think about what was so great about them. In Vienna, there were all these sites and any of the artwork could work in any of the locations. So therefore, they could be in any place in the world and work. When we got back, furlough almost immediately started getting put in place. And we were like, we’ve got the time now, let’s work this all out.

Luke Greer: With furlough, we figured we’re being paid to do jobs, essentially. So we spent that 9-5 routine just doing research and development on how to achieve it.

ED: I think for quite a while we were quite interested in using the same Klappenautomat style of vending machine they used in Vienna. But equally, those machines have a very specific association to the space in the country that they’re in, and they’re also very expensive. We were applying for Young Scot funding and I think the maximum amount you can get through that is £1,500. So we already knew immediately that we weren’t gonna be able to afford that machine.

LG: So we started thinking about what’s our familiar association with vending machines in this country. We’ve got tampon vending machines, condom vending machines, crisp vending machines. The problem with tampon and condom ones are they’re really small so we were basically just searching for a scaled-up version. Which is when we discovered the nappy vending machines.

CD: Speaking of the machine itself, there is this lovely, approachable element that the vending machine format brings to the artwork. It feels like because you’re not experiencing the work alongside the rules of an art gallery, that you get to have a bit more of a personal experience with the work and connection to it.

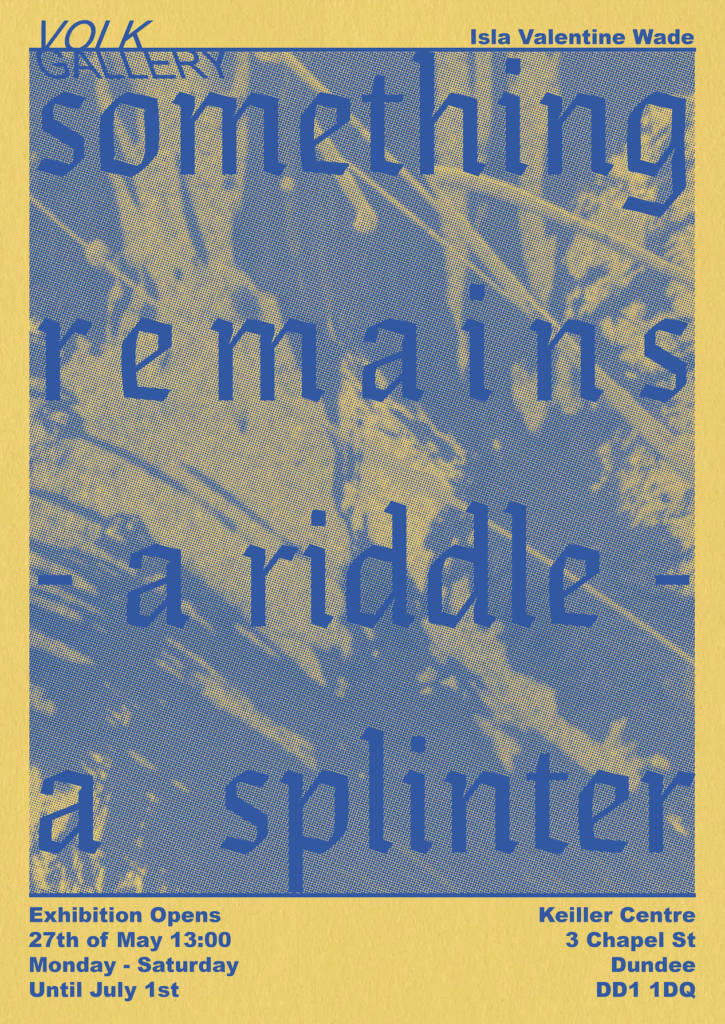

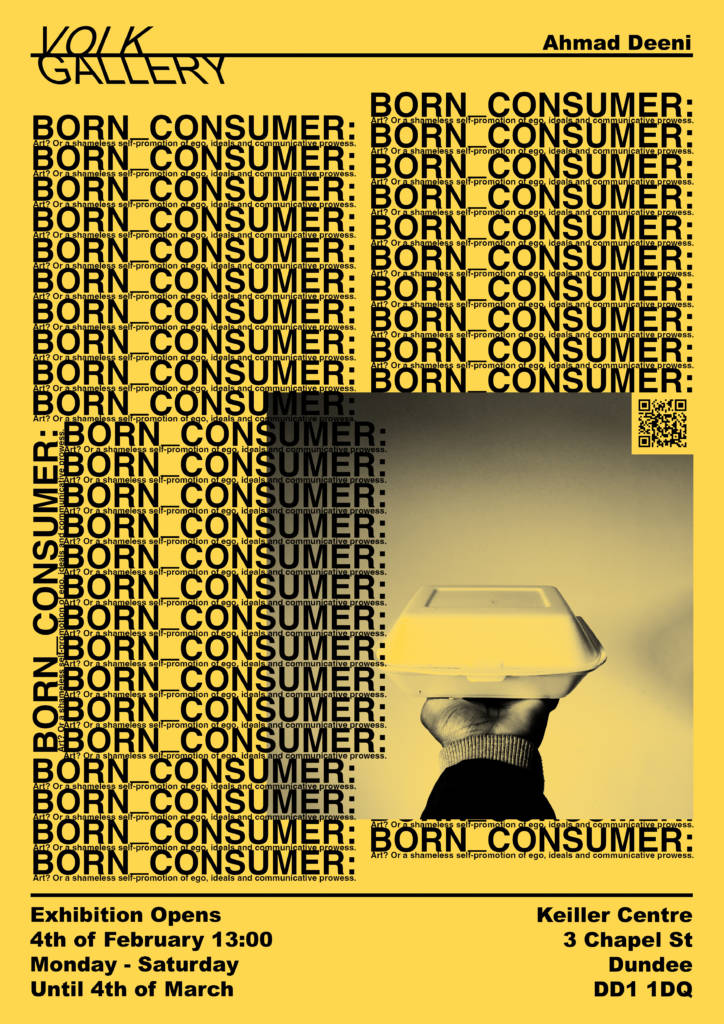

LG: There is that inherently fun thing of putting in your £3 and having that quite kinesthetic process where you get the “kidunk-kidunk-kidunk, whoosh”. I think it helps that Volk’s also got that mystery element to it too. The exhibition text we write will hint at aspects of the work – I guess it generally describes it without telling you specifically what it is, which is how I do the graphic design of the posters.

ED: I think that the process of using the machine also gives people a bit of reassurance that not all art has to be serious. Like, art can be fun lads!

CD: So you found the machine you wanted to use—how did you go about finding space?

LG: The council was really helpful for putting us in touch with others who could help.

ED: They were. They were great. And they initially put us in touch with the Overgate, which we weren’t 100% sure about because we wanted it to be as accessible as possible. Originally, we’d wanted to be outside. So that’s led us to going back to the council. And we’re like, oh, we’re not really sure about the Overgate. They were like, “Well, Angus Morton at the Keiller Centre is always game for a conversation, why don’t you have a chat with him?” And we arranged a meeting and we ended up chatting with him for about two or three hours in his little office. And afterwards, he very kindly went and spoke to the owners and they okay-ed us having a wall space. So that’s how we ended up in the Keiller Centre.

“It’s an example of cracking doors wide open and not isolating ourselves by creating artist-only spaces.”

CD: We often talk about space being the hardest thing to find for creative projects. How have you found being somewhere that I guess has more commercial interests in mind?

ED: I think overwhelmingly the team we have day-to-day contact with in the centre are absolutely incredible and so supportive of what we’re doing. I always shout out Jim, who’s our favourite security guard, but the whole security team is incredible. They look after Volk for us because at the end of the day, it’s a box with money in it on a wall. I think because Angus has worked there as long as the Keiller’s been the Keiller, he was just so passionate about doing what it takes to look after the space and make it last. Because we’re now in scary positions where you go in places like that and they don’t always last long.

LG: But I think because Angus went through the Dundee Design Festival too and really saw this big shift in what the Keiller Centre could be, he’s really driven to make that a more feasible thing. Commercial retail is in that really awkward space right now, so I guess it’s that classic thing of when spaces become useless for their previous function, artists come in and start utilising them and then eventually that area picks up and then the artists get pushed out. That used to be industrial spaces but now it’s old office buildings and shop fronts. We were conscious when finding a space for Volk that we wanted it to feel really accessible because a big part of it is sharing art in unexpected places. Thinking back to the design festival in the Keiller, I remember [Dundee-based ceramicist] Steph Liddle was making things in front of you at that and, although it’s quite uncomfortable to work like that, I think it’s a vital aspect for people who aren’t involved in the arts to be able to actually approach these things and go like “that looks like it’s really enjoyable just to do”. They begin to think about how to do these things, to start supporting the people who are doing these things. It’s an example of cracking doors wide open and not isolating ourselves by creating artist-only spaces. If the Keiller Centre did just become like an art centre, I think Volk oddly fails in a way. Like, if the Keiller really picked up and it’s all artist’s studios, do we shift somewhere else? Do we move to the Overgate, is that what happens?

ED: Yeah, it becomes a formal gallery suddenly, which is what Volk is pushing against.

LG: But I think that also comes with being connected with all the small businesses. With the Keiller, we don’t want people just coming in for Volk, we want to contribute to that entire experience. We don’t want artists to start becoming the people that shove people out of spaces.

ED: I think more of these commercial sectors need to be setting space aside for creative or community projects because all of these things can live together. We don’t have to be like, “This is the art centre. This is the food court.” We can all just mess it all up and not work in a straight line. And the Keiller Centre is a maze, like, let’s celebrate the maze. Let’s just roll with it. Who knows what you’re gonna come across around the corner?

CD: You’ve now been up and running for over a year—when you compare what it is now to what you planned it to be, how comparable is that? How much have you had to change?

ED: I’d say fairly comparable. There has been a bit of an evolution, because I think initially really set out to showcase contemporary visual art and we’ve now broadened that focus. We’re still a gallery but we understand that a gallery space shouldn’t be like “we only like this certain type of thing”. We can be a lot more experimental with it, which led us to commissioning someone like Ieva [Jankovska, Jeweller] where we really stretched what somebody terms their practices as and let loose a little bit.

CD: And what’s the public response been like to it?

LG: I think it’s been really positive!

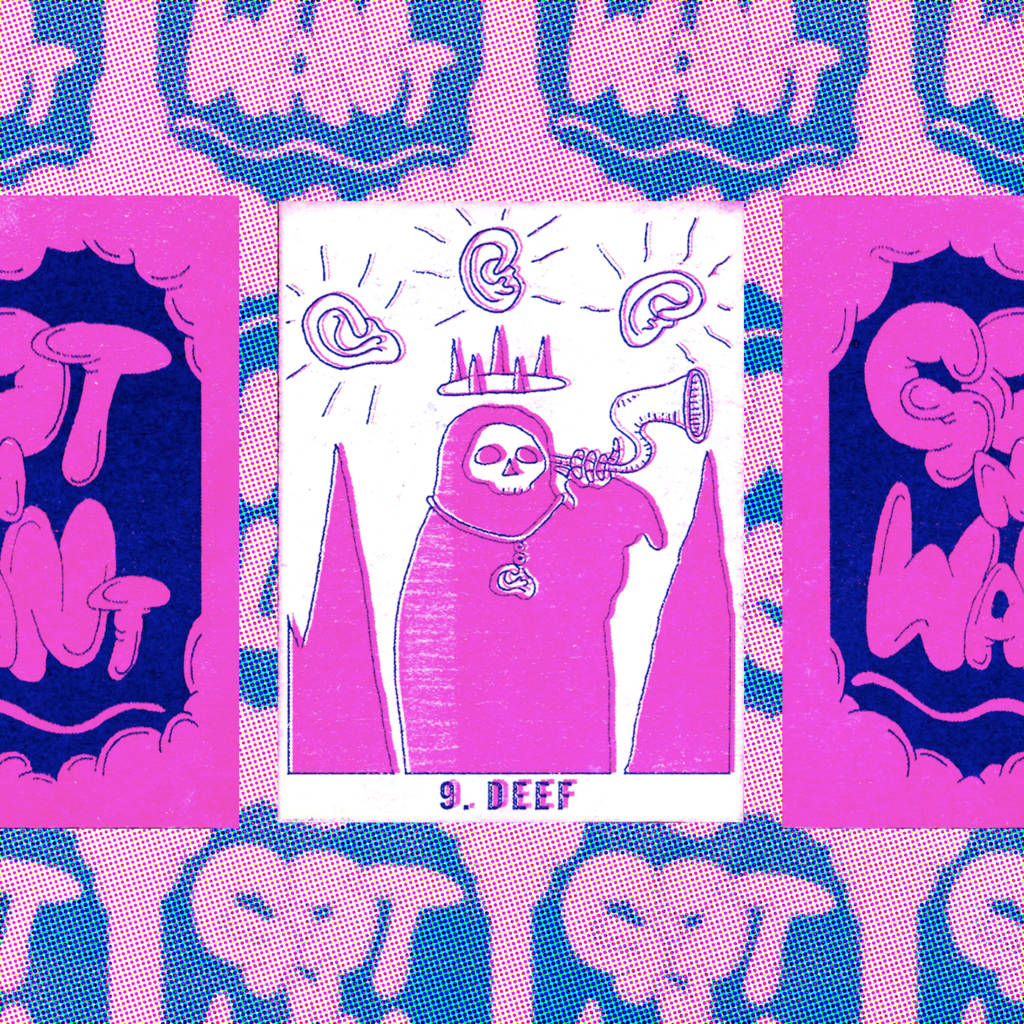

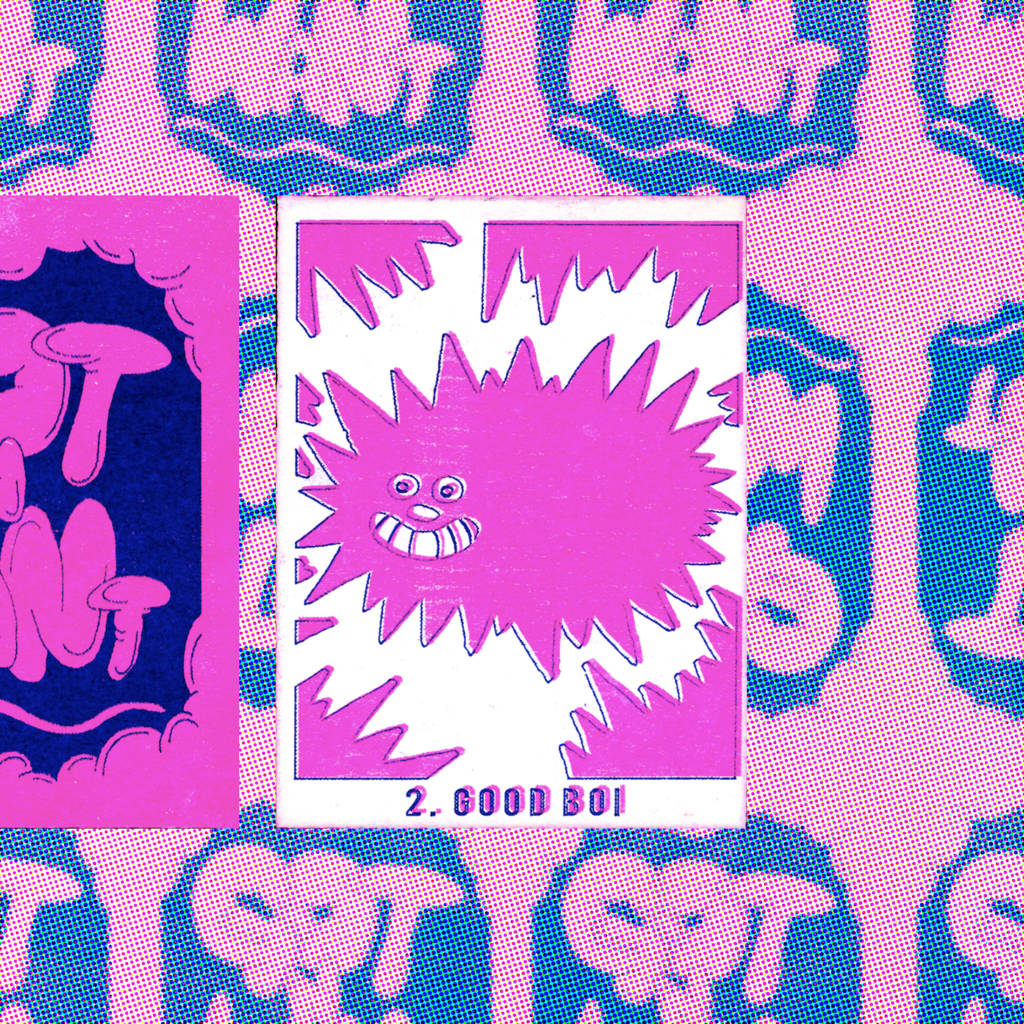

ED: Yeah, I think the response to all the artists’ work we’ve had has been amazing. I guess the trading cards were a really great example, loads of kids got really into it. There was a mother that reached out to Sean Wheelan who made the work on Instagram and was like “I’ve been three times to this machine, we’re missing one card, dear god please, we’ve got so many extra cards, I can’t go back” so Sean sent out an extra one to her. We had somebody else put a sticker on the machine too that was like “I’ve got 6 of number X, does anybody need them? Can I swap for 9, DM me on Instagram, here’s my handle”. There’ve been lots of lovely things like that.

LG: That was in January too, which is notoriously a dead month for the arts but somehow Volk bypassed that.

ED: Yeah, it was amazing to watch and I guess we just didn’t really think about who would be interested in that. Because it’s not our job to think about “why are we doing this?” The whole point of it is to be open to whatever the artist wants to explore.

CD: You’re both busy working on other jobs, and on other passion projects too. How do you find fitting Volk in around your schedules?

LG: Well, I think the great thing about Volk in the way we designed it was, to an extent, a set it and forget it situation. We don’t have to invigilate a gallery space, it’s very much a case of we do all that behind-the-scenes stuff, designing posters, liaising with artists, coordinating the programme, graphic design and all that. The artist does their bit, and we’ll get this big bundle of artworks, usually through the post to put in the machine and close it up and then check in on it. In some ways, it’s a really low-stress project. And in other ways, it can be super high stress.

ED: Yeah, it’s manageable and it sits really nicely with the other work we do. But I still work full time. That mostly is Monday to Friday, and I’m always here for the weekend, which is great. But Luke’s freelance so his hours are all over the place, and then we also have [a quarterly arts publication] Windfall* that we both work on too…

CD: It’s a lot of spinning plates you’re balancing. What motivates you to keep going with these projects?

LG: I mean, I don’t think anyone ever starts a project like Volk or Windfall* with even the vaguest notion that they’re going to make a ton of money, even if there is actually profit involved.

ED: Jesus Christ no! If we went into projects only if we were going to get paid for them, we would’ve given up two days in.

LG: My primary job is running Yalla Riso and still, even though the intent on that should be a lot more focussed on generating revenue, that is so far off the intention of that too. I guess I’m still figuring out how to weigh up how these things balance and become profitable enough to earn a good living. It’s a really difficult one, and I don’t think, especially right now in the climate we’re in, that that’s actually that feasible.

ED: It’s not like somebody’s done this all before and you have a model to follow, it’s very individual.

LG: I think the motivating thing for us is we’ve got the intention and belief that art should be really accessible in a really public way whilst also being able to enable artists to be compensated to an extent for their time. So for us, the focus is how can we realise that, whilst also balancing our personal schedules. I think Volk managed to fall into that really nicely where it’s fairly low stress. And we get tagged on Instagram all the time by people who’ve gone and picked stuff up like “This is amazing, look at this!” Just all these lovely wee things are motivating. But I think the only way that we could work in a sustained long-term way and see projects like this actually give back in a really sociable, tangible sense is to have larger infrastructural changes where you have a Universal Basic Income. Where suddenly, we’re not panicking at the end of every month and we can turn down occasional projects and jobs that we don’t want to do in order to actually start developing ideas.

ED: Which is why we try to be as open and honest as possible when commissioning artists for Volk. We try to make it ultimately clear to the artist that we are not paying them very much money, and therefore we are not expecting them to make the Mona Lisa, you know? If somebody comes back with work they’ve already made and maybe they’ve shown one version of it, fucking great. We’re happy for Volk to be part of their process.

LG: We’re a space for a pet project. It gives them space to trial things and do odd bits and bobs.

CD: So what’s the next step for Volk?

LG: We’re at the early stages of thinking about adding another location up in Aberdeen. Volk is irrevocably tied to scale; the reason the artist has a meagre budget of just £50 to make the things is because we charge £3 a time, with £1 going to pay the artist for their time, £1 going to a material fee and in theory £1 as the backup emergency fee, which is incredibly important. So that £50 is how much money we can make from it. The only way we can feasibly see to expand that is to have more things in more places.

ED: It also means there’s more work for the same amount of thinking from the artist. But also, what a cool thing to be able to say to artists you can exhibit in two cities at the same time!

LG: Or even, hey you can exhibit across the whole of Scotland at the same time.

ED: We would love the fee to reflect that amount of work they’re doing. But it’s also just an understanding of who we are, what money we’re working with and just trying to be as transparent as we possibly can be with these. Because I guess at the end of the day we’re volunteering our time to do these things. They are our babies and our projects and we are enthusiastic about them but we’re not being paid for this, so there’s only so much time you can give to them.

LG: Which is why we’re actively talking to other people up in Aberdeen, like The Worm and Look Again and really feeling out how we can make it more collective orientated. We want to really spread it out and make it less like Lizzie and I dictating what everyone is going to look at and enjoy. The more voices you bring to the table, the better it is.

ED: Totally, and have a bit of a team going on to manage it all too.

“Other people are holding you accountable here, but in the most encouraging way. There is nothing ingenuine, it’s like someone you saw in passing wants to see you succeed.”

CD: You both moved here to study at DJCAD and then stayed. How have you found working as creative people in the city?

LG: I think because there isn’t that much arts infrastructure in the city– given how small the city is it’s actually pretty good– but comparatively to Glasgow or Edinburgh, it’s tiny. But I think that’s actually quite beneficial for us up here, because we don’t have that same competitive thing, it’s much more collegiate.

ED: Totally, I’ve said this like multiple times and I’ll keep on saying it, but Dundee is the city where you can talk to someone in passing about something after having a pint and say things like “Oh we totally want to bring Volk to Aberdeen” and then two weeks later that person will be like “Oh did you apply for that funding yet?” Other people are holding you accountable, but in the most encouraging way. There is nothing ingenuine, it’s like someone you saw in passing wants to see you succeed.

LG: I think it’s just about not being afraid of failure and Dundee is quite encouraging of that, like if it goes wrong, it’s fine. You tried something, that’s the important thing.

CD: Speaking of Dundee, what is it that you’d love to see happening in the city in the next few years?

LG: I think what we’d really love to see is a development of these more public facing spaces of arts-related businesses. So things like sculpture workshops, riso printers, picture framers, shared working spaces, a zine library; the kind of places that allow artists and creatives to have conversations in a very natural setting that also facilitate making work within the city. There are aspects of it already, we’ve got DCA Print Studio which is a great resource, Dundee Ceramics Workshop and spaces like GENERATORprojects and Chainworks but unifying these things under one roof would be amazing.

ED: Yeah, and I mean Tin Roof when it was around was a wonder. I think what it was trying to do was an outlier at the time and unfortunately still would be, and that’s a problem. But just somewhere that can be a space for creatives of all kinds to be together. I know that it’s not always realistic to be like “we’re going to recreate the university studio experience” but we could take that spirit into a more public space.

LG: Also being conscious of not being some exclusive space that only artists feel like they can use, making sure it’s a really public and accessible space that people actually want to come to on a daily basis. Things like having a cafe go a hell of a long way for getting people to come in.

ED: And even having businesses within there that have people coming in too—like a framers for example, that people would come in and use.

LG: Or even somewhere to get keys cut…

ED: Exactly, and then we’re back to the Keiller Centre.

LG: I think really it’s about getting everyone’s businesses out of spare rooms in their flats and actually into spaces, that’d be amazing! One day…

If you would like to support us in creating even better content, please consider joining or supporting our Amps Community.